Recently Like Stories of Old put out a video titled “How modern audiences are failing cinema”. The thrust of that title has perturbed me over the last week, so much so that I felt compelled to write this piece to sort out my own thoughts. It sounds the death knell of how regular audiences seem to be unable or unwilling to engage with cinema outside the mainstream. You can watch the video here:

I have been struggling to understand what LSOO is hoping to achieve with this video. His arguments are scattershot, but his provocations are incisive, possibly even unknowingly insidious. Telling an entire group of people they are “failing” is a polarising charge. How can one “fail cinema”?

In my opinion, the essential argument here feels a little irresponsible considering LSOO’s reach and cache among a large global audience of cinephiles. It’s a message that riles people up, draws battle lines and creates antagonism, no matter the gentleness of his soft, droll voice. As advocates for cinema, I think he and we can do better.

In writing this piece, I actually find myself largely in agreement with LSOO and the nuances he brings to each of his points. Unfortunately, I think he has placed many contradictions and uncertain questions under the single umbrella of a provocative title, which has oversimplified his position. There’s a knowing messiness to LSOO’s underlying arguments, which is by design because he is equally searching for the right answers, sometimes the right questions, to his own discomfort with modern audiences.

How do you “fail” cinema?

Films themselves are inert, conceptual objects. They have no feelings or desires. There are no obligations to appreciate or understand a film. Neither do we have obligations to the filmmakers who have made them. The cinematic conversation is only between film and audience. A film’s life is dependent on the zeitgeist that sustains it. Culture has no obligation to film. All art is a part of culture, until it isn’t. Cinema can die. It dies not because we fail it, or because the films themselves become worse. I believe cinema dies when we stop communing with each other about the stories they contain.

There’s a false dichotomy here of the “anti-intellectual” camp and the “faux-intellectual” camp. Notice how the names of each side is what each side calls the other. We are making enemies of each other, not because we hate each other, but because we want to protect our corner of cinema and our way of engaging with it. It’s tribalism. Nobody is wrong in their approach in cinema, and yet we find the need to defend ourselves.

While I cannot quite pinpoint LSOO’s main point, I thought I would go through his supporting arguments to poke at the points he is swirling around:

Relatability

LSOO’s point here seems to be the inverse of the title of his video. He argues that cinema, both mainstream and independent, is failing audiences by leaning into relatability in trite and generic ways. He argues that #literallyme memes show a superficial understanding of characters in films and that audiences who engage in such a fashion are maintaining a “wilful ignorance.”

To try to guess at what’s happening behind the minds of people who make and engage with #literallyme memes is pretty presumptuous. Sure, maybe some are engaging with cinema in a vapid, superficial way, but we cannot paint an entire audience so nonchalantly. For example, people making political memes aren’t doing it because they don’t care. They do it because they do care, but the world is absolutely mental, and sometimes you need to shitpost to cope. Cinema is not immune to that. While cinema can be a form utilised for the discovery of complex meaning, or posing difficult questions, it has largely been marketed and used as an easy means of escapism. Relatability gives audiences an easy way to “feel good.”

#literallyme is also a signal of identity and meaning formulation, sometimes ironically so. Which is what we do when we watch any film. We are trying to see ourselves in them, which can be deep or superficial, and that journey is personal. Not everyone’s means of engaging with cinema is writing long essays or creating analytical video essays. Sometimes the search for significance within a film is private.

My sister, for example, would not proclaim to be a cinephile, and she found herself loving Past Lives. While I did not appreciate the film as much as she did, merely knowing that it meant something to her in a profound way helped me understand what she cared about and responded to as a person. Films can be a medium of communication with each other. A Letterboxd four favourites is a means of forming identity and a projection of taste.

The irony of this section is that LSOO’s video similarly invokes a “he’s just like me frfr'' response from the so-called intellectual cinemagoer. He falls right into the same trap. His content only exists because there is an audience who can relate to it. Relatability is not a trap, of course we tend to consume content we can relate to. All people want to find their tribe. Everyone wants to feel comfortable. Big corporations and indie filmmakers lean into relatability, whether intentionally or not, because they need an audience to justify the existence of their product. Whether that push towards relatability is good or bad is dependent on how the audiences react to the product. It’s a matter of market and social forces. As much as we want to think of film as a significant art form, it is still a product. Products need customers.

If we are worried about an overall engagement with cinema, we should not be gate-keeping the way others engage with it, regardless of which camp you come from. Cinema is vast and diverse. We can win together. However, I also understand that LSOO wants to encourage audiences to seek cinema that is less relatable to them because of what they can gain from it. I agree, but I think adopting an accusatory angle against modern audiences is a needlessly antagonistic way of beginning that process.

Cinema as self-righteous moralism

In this section, LSOO finds difficulty with the way we use the action of consumption as a means of self actualisation, and that we think of the movies we watch, or the movies we deem “good” as moral actions. Watching a “good” movie becomes a personal moral “good” as does attacking a “morally bad” movie. Generally, LSOO venerates the more “difficult” movies with complex moral positions, films like Killers of the Flower Moon, Tár, May December, and The Zone of Interest. He thinks general audiences avoid or even dislike these films because they require one to “invite conflict into one’s inner being”, a discomforting experience compared to the easily relatable “morally good” films that people can use to self actualise.

Even though I enjoy and admire these types of films that create uncomfortable moral positions, I find that LSOO’s perspective thinks of these films as objectively better cinematic experiences. He positions intellectual or moral complexity above emotional engagement. While that can absolutely be his personal taste which I cannot discredit, it does not mean we can denigrate the way others prefer to engage with film. I could argue that his perspective extols these films because complexity fulfils a certain “moral good” in his act of media consumption. He posits that “discussion and conflict” are a fundamental part of how we appreciate the cinematic medium that we are now losing, but I don’t think that is necessarily true. Some films will evoke more discussion and some will create more conflict among their audiences, but it does not mean it is a “fundamental” outcome of any film.

Do I wish more mainstream audiences could give these more “complex” films a chance? Do I agree that “human beings are complicated” and that “history is messy”? Yes, of course! However, it is also totally okay to love movies that make us feel “morally good.” For the longest time, Bicycle Thieves sat in the top films in the Sight and Sound top movies polls. It’s a simple, sentimental melodrama about the plight of the working class. There’s very little complicated or complex about it, but people love it for how it makes them feel. Loving it also signals that they care for the people who are struggling below the poverty line. I believe there’s a moral action here, but who is wielding it? Is the audience using the film to prove their moral good? Or has the film used powerful tools of cinema that can evoke empathy to engender an audience toward a cause for moral good?

To tackle a more recent example that LSOO references in his video: Does America Ferrera’s monologue in Barbie merely echo a general sentiment that people find easily relatable, or does it effectively create a sentiment that people find easily relatable resulting in a winning film critically and commercially? Chicken, egg, etc. It is difficult to ascertain the intent in the making of these films, but we know films are largely empathy machines which generally appeal toward a sense of moral good, whether generic or novel. Sometimes those tools can be utilised for morally bad aims, some films can be “problematic.” It is up to us to talk about these things and that can be the discussion and conflict that we can have, regardless of the kind of films that are part of the conversation.

Overwhelming constant stimulants

I am the last person that will disagree with LSOO’s prevailing sentiment here. There’s too much content, too much noise, too much choice, and we defer to algorithms to make our choices (leaning towards relatable, catered for you type content) because the paradox of choice is paralysing. The debilitating effect of this overwhelming noise is that we, as audiences, cannot carve out the space to engage with something more complex or demanding of our attention. We rather wilfully discard our attention in a thousand pieces to the most convenient bidder because it is easier. We present the choices between mindlessly scrolling on TikTok, and spending 2 hours in a movie theatre as equal propositions.

I agree that this is a huge problem, but it is clear the real villains are not the audiences but the corporations that value our attention and are clamouring to claim it. However, I think we forget that our attention does not need to be given. Sometimes we need to spend that time and energy on ourselves. We lead stressful lives and events that we demand “escapism” from, or “mindless comfort” to cope with, but maybe the answer is not mindless comfort, and maybe it also is not cinema. Seeking good cinema is not the solution to “bad content”, and audiences are also not the problem. To put it in blunt and bleak terms, the problem is the context we currently live in can feel hopelessly fucked. Our attention is shredded to bits, and our ability to commune appropriately with each other is dulled. Cinema is not the salve.

I also see the irony here writing my little newsletter hoping to find my own little audience, as another drop in the content bucket that’s already completely overflowing. If you’re reading, I appreciate you and the attention you’re granting me. I hope these pieces provide a sort of mindful comfort. Anyway, here comes my subscribe button:

Towards true nourishment

At the opening of this section, LSOO declares there is no “absolute death of cinematic curiosity”, a rebuke of his original alarmist title: “The Death of Cinematic Curiosity” (which is the reason I clicked on the video). LSOO admits he is also contending with his own existential crisis with cinema, finding himself falling into the same traps as the “modern audience” he is painting, and hoping to immerse himself in better cinema. The video is not really about other people.

He’s disappointed that he himself has recently indulged in popcorn entertainment instead of more “nourishing” and difficult complex films. Tom, there’s no need to feel shameful for your diet of cinema. There is cinema for every moment, and sometimes escapism or relatability is the answer. You can contain multitudes, my guy. There’s no need to be so hard on yourself, or on others.

It’s why I am frustrated by something as simple as the title of a YouTube video. The title pins the blame when the video does not. Even for Tom, he is beholden to the algorithm, stoking emotional flames for clicks. I guess it has worked on me to engage with it to such a high degree, but the litany of YouTube comments show many who only grasp the emotionally incisive main point but none of the nuances he tries to pair with the video.

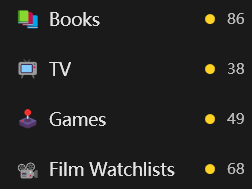

Still, I find myself also commiserating with Tom’s journey here, also realising that there’s content I consume, be it television, video games, or film, in a mindless fashion. I am always culling the need to consume. My lists grow ever longer, and every once in a while I have to aggressively cut them down or the pressure to do it all becomes too stressful. Heck, I’ve been trying to completely quit television because of the outsized time commitment but the desire to keep up with the latest dragons can be hard to kill.

If there’s anything I implore others to think about, is the need to reconsider our relationship with the content we consume and to be a little more mindful with how we spend our time. This is completely generic, and could have nothing to do with cinema, but I think spending the time to think about what is important to oneself is a necessary act of identity forming. The most important algorithm for deciding how to spend your time is in your skull: cultivate and listen to it.

I find my own discovery of cinema as a hobby to be equally a crutch to escape, even if the films I aim to watch are supposedly more complex or nourishing. Films are inert. The value they produce is aligned with the effort and attention you pour into them. A supposedly good, complex, and nourishing film can still be used for “mindless comfort.” This year, I decided I wanted to watch fewer films, but spend more time engaging or thinking about them to glean better insight. It has little to do with the films themselves, or their inherent quality, but with my approach to the medium. This is something no one else has control over, not the movies, not the audiences, just me.

I say Tom’s argument is meandering, but I know my response here feels similar. We both see an issue with how we, as a larger general audience, engage with cinema, but we don’t know what the right solutions are. Maybe we can only be observers to how attitudes shift, and any agency we hope to exercise in shaping those shifts is lacking.

Some films will die, despite their excellence. We can try our best to champion them to those that remain unaware of them, or even unwilling to engage. We need to extend hands across these supposed battle lines and invite others in. Compel them to give them a shot. If it doesn’t work out, so be it. Most importantly, we need to share cinema, not because it makes us feel good about our taste, but because we think cinema is good for others. Like I said earlier in this piece, I believe cinema dies when we stop communing with each other. This year, I’ve come to realise how important community is when it comes to any hobby or interest, niche or otherwise. People sustain and nourish each other, not cinema. It’s difficult to appreciate cinema alone, find others.

We can’t fail cinema, but we sure as hell can fail each other. Be kind.

Notes

I added photos mostly to break up text, but they’re not doing much else. Would a wall of text be equally digestible? Someone let me know!

This turned out really long which I was not expecting at all! I think Like Stories of Old tapped on something latent that had also been bothering me.

Deep Cut just released an episode on Cure (1997) , now that’s a film that’s complex and challenging!